Abstract

This post explores the dynamics and challenges local churches face during periods of growth, emphasizing the importance of creating effective systems and frameworks to manage these changes. It highlights the distinction between goals and results, emphasizing that church growth is not the ultimate objective but a byproduct of deeper spiritual engagement and community service.

In the Church world, we often confuse the fruit for the goal. Here are some examples:

- Church growth is not the goal but the fruit. The goal is prayerful partnering with the Holy Spirit to build an infrastructure that will care for, instruct, and disciple members and attendees and strategically serve the surrounding community.

- The church is not the goal but the fruit of kingdom ministry. This is why Jesus stayed 40 days after the resurrection and spoke “of the things concerning the kingdom of God” (Acts 2:3b).

- The Great Commission is not the goal but the fruit of active and passionate engagement with the Great Commandment. This is stated well in the opening lines of the Westminster Shorter Catechism, “What is the chief end of [humankind]?” The catechist is then to respond, “[Humankind’s] chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

- Obedience is not the goal but the fruit of active and ongoing surrender to God’s empowering grace, which will do in us and through us what we cannot do on our own. Paul navigates this as he moves from the end of Romans 7 into Romans 8.

With that said, let’s consider the art of servicing growth and momentum in the local church…

As Churches Grow Dynamics Change

When churches are smaller, relationships carry things; in larger churches competencies need to carry things, and organizational systems, including policies and procedures, need to be re/designed and implemented to correspond to growth. The lack of appropriate systems can create a condition of ambiguity that increases the chances for unnecessary conflict to erupt. In the larger church, the guests and visitors are different kinds of “shoppers.” Relational equity that the staff once enjoyed when the church was smaller, when all were treated as part of the family, is replaced by the demands for performance and competency that are much more exacting. A larger and larger percentage of the congregation is going to be “competency expecting,” placing sometimes unrealistic demands on the staff that are not mitigated by the relational coziness that had been enjoyed by the older, earlier congregants.

If there are no agreed-upon updated operational systems it means leaders have not engaged in pre-thinking different scenarios, which introduces unnecessary anxiety into the system, which can also lead to conflict, which can be the result of unmet expectations because the church has overpromised and underdelivered.

In the larger church, there is a more fragile system to deal with. After growth spurts it’s very common for some people not to make the transition to a larger church where they won’t know everyone. Some people will hunger for the more relational approach of the past. This can also cause conflicts if it’s not managed well. Typically, when a church grows (past barriers), some of the staff, who cannot migrate from minister roles to team building equipper roles, choose to go back to smaller churches because the satisfactions they need and the relationships they desire are found in smaller churches, which is not wrong. This discontinuity can also cause conflict if not managed well. There is a saying in family systems theory that the presenting issues are rarely the real issue. Many of these conflicts can be resolved through a growing understanding of family systems theory. It is helpful to remember that all conflict is an opportunity—to know God and one another better.

There Are Mandatory Disciplines for Serving Momentum

Surges will continue if leaders service them. However, the growth catapults the congregation into a new dilemma. In smaller congregations, most problems are solved informally by the way people behave. The demands are not such that they require a systems style of thinking. In a larger church, leaders can’t ignore problems and have them go away.

After a season of growth, a church will develop “stretch marks.” The church may have more people than their systems are capable of assimilating (e.g. not enough small groups or enough leaders in place) and the church can get caught between two systems of ministry delivery. There’s a system of ministry delivery at the Sunday service level that remains basically constant (music, preaching, CM, etc.). The pulpit looks the same to everybody. What changes, however, are the things that are done under the umbrella of the Sunday service. Is the ministry being done by professionals or volunteers? In a larger church, the ministry needs to be increasingly mediated by volunteers. There is a need to create multiple systems that are suitable for volunteers to do the work of ministry. Volunteers do not have the same proficiencies as professionals have (e.g., teaching skills, Bible knowledge, etc.). Real ministry increasingly needs to be accomplished in smaller groups where conversational and facilitation skills are developed. There is a need, at that point, to create far more structures/systems that are led by lay people with lay levels of skill and higher relationship factors to bring people along. The proficiencies needed are less because there are higher quantities of relationships involved. (People will survive while their lay leaders are searching out answers for them; whereas, if a professional doesn’t have an answer for them, they will be less likely to stay connected.) Attendees are bonded by their relationships – it’s a social factor that attracts people, holds them, works with them, and supports them over time.

The staff is required to move from providing ministry to assuring that ministry is provided. Thus, a BIG shift must occur. A whole new delivery infrastructure must be configured. The staff needs to move from being “all-powerful,” super-trained, super-competent, “do most of the ministry” people to making sure that the lay leaders can operate effectively in loving and caring for people. This requires that staff adopt the technology of facilitating ministry through building teams. The hindrance is that it’s counterintuitive. The staff will have to lose the ability to minister alone and use every direct ministry opportunity to train lay people for ministry. The staff (and board) needs to move from a “shepherd” mentality to a “rancher” mentality.

Stephen Covey wrote about the difference between “production” and “production capacity” (PC).[1] Consider how much production a staff or elder is capable of. Every once in a while s/he can double their production, but only for the short-term—and then s/he needs some recovery time. But if staff can “clone” themselves, they can double, triple, quadruple, etc. their production capacity. Eventually, this can lead to exponential growth. It’s a strategy of lay ministry enlargement that we see in 2 Timothy 2:2, which states, “The things which you have heard from me in the presence of many witnesses, entrust these to faithful [people] who will be able to teach others also.”

Again, the staff needs to see themselves as “minister-makers” instead of ministers. There is a difference between ministers and leaders; ministers build people and leaders build groups, or teams, of people. It’s like the wings of a bird, the church needs both to fly straight. This doesn’t happen through proclamation alone; it involves proactively building a leadership development pipeline along with discipleship/spiritual formation pathways. The hand-off to lay leaders occurs in steps. Lay leaders are the key to maximizing a church’s potential. So, the question becomes, “How will we recruit, train, deploy, mentor, and nurture lay leaders to a high level of competence so that they’re actually caring for people reliably and effectively?” And it is wise to help leaders develop skills for life, not just church work.

There is a need to define and update the roles of both vocational and volunteer staff with clarity so that all will see that lay leadership is a privilege they are capable of. (Not to see themselves as “waterboys” for the professionals but to see themselves as ministry leaders in their own right.) Systems must be in place to provide strategic support to lay leaders.

Leaders need to be coached to replace themselves. New leaders are incubated as attention is given to the development of apprentices. Give prayerful and purposeful attention to replicating leaders. The best place to train a leader is at the shoulder or elbow of another leader. Coaching is only effective when apprentices are present. Wherever there’s the absence of apprentices, the coaching is deficient.

A Systems Approach to Leadership

One of the keys to functioning in a healthy manner as a church is for the leaders to look at the church as a system rather than a collection of isolated people.”[2] As stated earlier, a lack of awareness of the church as a family system could cause a congregation in times of conflict to focus on symptoms rather than the more complex systemic issues.

Churches exhibit both organizational and family characteristics. In both cases, the challenge is to think systematically about the way problems arise and see both successes and problems as a sum of the whole, rather than as individual parts.[3]

Six family system theory concepts frequently affecting the church:

- Maintenance of origins (Homeostasis) — the tendency to habitually preserve principles and practices within the organization, even when they are detrimental.

- Problems-symptoms/root (Process and Content) — the incapability of leaders solving a problem without first understanding the root source of the problem.[4]

- Non-anxious presence — the ability of the leader to define his or her life apart from the surrounding pressures of ministry, thus freeing the leader to have a clear head when dealing with problems.

- Over responsibility (Overfunctioning) — the tendency for leaders to take responsibility for problems for which they are not responsible, thus allowing others to maintain irresponsible behavior patterns.

- Triangulation of relationships — when two people, are at odds with one another one (or both) triangle one or more people into the problem and it magnifies and multiplies the conflict. Triangulation is a form of gossip.

- Identified patient (or scapegoat) — a leader who begins to exhibit the symptoms of a dysfunctional system can be made to appear to be the problem when in reality the problem is the system that created the symptoms.[5]

Organizationally, churches may be viewed from a series of perspectives:

- Structural factors — including roles, goals, and the structures and systems that make the church work.

- Relational factors — focusing on developing a fit between people, their gifts/skills, and the jobs they do.

- Political factors — involving power, conflict, control, and coalitions that form within the church.

- Cultural factors — involving the shared values, corporate stories, heroes, and milestones that give a corporate culture to the organization.[6] Each of the system concepts and organizational perspectives gives important clues to understanding the life of the church.

Governance Issues

There are many different ways to govern a church. A policy-based governance model occurs when the church board makes decisions through the use of clear and consistent policy, based on biblical directives. Policies are the beliefs and values that consistently guide or direct how a church board arrives at decision-making.

Policies are articulated carefully as the board prayerfully considers what the Holy Spirit is saying to them in their unique context and seeks to build the infrastructure to accomplish the vision.

The fundamental principles of a policy-based governance model have their roots in biblical principles including:

- Servant Leadership

- Mutual Accountability

- Empowerment with constraint

- Clarity of Values

- Integrity

- Role Clarity

- Distinguishing between ‘ends’ (board role) and ‘means’ (staff role)

Administration Issues

As churches grow larger, the staff needs to learn how to do things that boards used to do when the church was smaller. It used to be that the board managed everything, and the staff did the ministry. As the church grows and develops, boards need to look at policy and approval issues while the staff does the planning and managing. The ministry is done by the lay leaders who are under the care and development of the staff.

A very significant shift occurs when a smaller church becomes a larger church. In the larger church the board oversees, the staff leads and manages, and members do the “work of the ministry” (Eph. 4). In the smaller church the board leads and manages, the staff does the ministry, and the lay people receive the ministry. The larger church paradigm is an essential shift in thinking. Administration must be placed around what the Holy Spirit wants and is doing in a congregation. The aim is to protect koinōnía so that it can continue to move the church forward.

Initial Goals for Staff Members in the Larger Church

Once updated role descriptions and specific goals and objectives are established the Executive Pastor’s role is to serve the staff and the leaders by coaching/equipping/resourcing them toward the accomplishment of the mission and vision of the church, as well to direct them toward the fulfillment of their own personal calling and unique contributions to the kingdom of God.

A system of regular developmental performance reviews based on their capacity to build and oversee ministry teams needs to be established.

A system for the staff to report on both their maintenance goals as well as their proactive goals will help to keep everyone on the same page. In many churches, the staff will spend around 90% of their time doing ministry and around 10% equipping others to accomplish ministry. In a larger church, those percentages should be reversed over an agreed-upon time frame.

A lack of organizational systems can significantly contribute to workplace conflict in several ways:

- Unclear Roles and Responsibilities: When an organization lacks clear systems for defining and communicating roles and responsibilities, it often leads to:

- Staffing ambiguities: Employees may be unsure who is responsible for specific tasks or decisions, leading to conflict over ownership and accountability.

- Overlap in duties: Multiple people may end up trying to do the same work, causing frustration and inefficiency.

- Tasks falling through the cracks: Important responsibilities may be neglected because of a lack of clarity.

Ninety+ percent of churches need to improve their communication channels. Without proper communication systems in place:

- Information silos can develop, where departments or teams where crucial information is not passed along.

- Misunderstandings become more common due to incomplete or inaccurate information being passed along.

- Lack of transparency can breed mistrust and suspicion among staff (and congregants).

In the absence of structured resource management systems there will almost always be resource allocation issues:

- Competition for limited resources intensifies, as departments contend for budget, personnel, or equipment without clear allocation processes.

- Perceived inequitable distribution of resources can lead to resentment and conflict between teams or individuals.

Poorly defined or inconsistent performance management systems can result in:

- Lack of common performance standards across different departments or roles can lead to perceived unfairness.

- Unclear criteria for promotions or raises can cause frustration among employees.

- Ineffective feedback mechanisms, leave employees unsure about their performance and career progression.

Without clear decision-making systems:

- Power struggles may emerge as individuals or departments seek to influence decisions.

- Delayed or inconsistent decisions can create uncertainty and frustration among team members.

- Lack of buy-in for decisions made without proper collaboration or transparency.

The absence of conflict resolution policies and systems can lead to:

- Unresolved conflicts fester and escalate over time.

- Inconsistent handling of disputes creates perceptions of favoritism or unfairness.

- Avoidance of addressing conflicts, resulting in decreased productivity and morale.

Conclusion

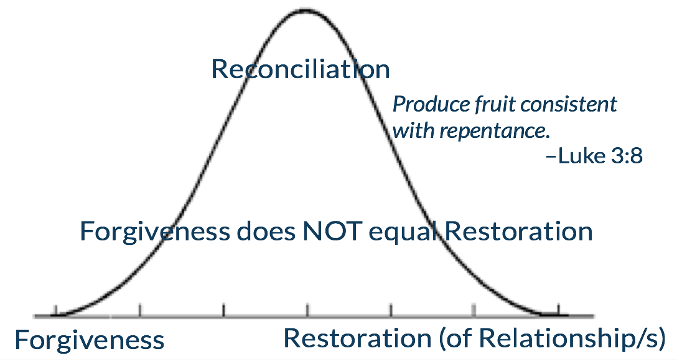

When we mistake the biblical fruit for organizational goals we may miss out on the interior growth that is necessary for long-term effectiveness in church life. With that being said, churches are wise to implement clear organizational systems, policies, and procedures that address these infrastructure areas, which can significantly reduce the potential for conflict and create a more harmonious and productive work environment. Effective systems provide structure, clarity, appropriate accountability, and fairness, which are essential for minimizing workplace conflicts and fostering collaboration.

[1] Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Simon & Schuster, 1989: 54, 109, 138, 243.

[2] Ronald Richardson, Creating a Healthier Church: Family Systems Theory, Leadership, and Congregational Life, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996: 26.

[3] Edwin H. Friedman, Generation to Generation, Guilford Press, 1985:216.

[4] Tim Keller referred to this as “the sin beneath the sin.”

[5] Woodrow Kroll, The Vanishing Ministry, Kregel, 1991:32.

[6] Malphurs, Leading Leaders: 118.